Everyone has their favorite movie monster…right?

The culture at large has had a long on-again, off-again love affair with vampires. Every few years, it seems, another toothy romance comes around and sweeps us off our feet. Our interest in zombies is perhaps the most abiding, with long-running series and films of shambling corpses from all corners of the world. We love ghosts, friendly or otherwise, and never seem to tire of watching demons crawl inside unsuspecting children or creepy looking dolls.

But the monster I’ve always loved most is the perpetual underdog of the horror community: the werewolf.

Werewolf films are essentially slasher films with a bit of magic, except the slasher is the object of both our fear and our sympathy (werewolves tend to forget what they were up to at night once the sun comes up). They also present the best opportunity for innovative effects: the transformation. But mostly, I think, they possess the same quality that draws me to characters like Dr. Jekyll and The Hulk: the question of what would happen if the darkest aspects of our nature were let off the leash.

In the long history of movie monsters (starting with Peter Wegener’s Der Golem in 1915) werewolves have always had an honorary seat at the table, but they rarely take center stage. The fact is there just aren’t as many good, quality werewolf movies as there are movies about vampires, zombies, ghosts, demons, aliens, or arguably even mummies. There isn’t a lupine literary masterwork to draw from as in Bram Stoker’s Dracula or Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In fact, perhaps the most well-known werewolf movies out there are the puberty satire Teen Wolf, where most of the action takes place on the basketball court, and the Twilight series, where the wolf plays heartsick second fiddle to the sparkly bloodsucker. Ryan Gosling has long been rumored to take a stab at this monster with director Derek Cianfrance, but when exactly that might actually happen isn’t clear. Until that time, werewolves will be waiting on the sidelines, as they’ve done for my entire lifetime. There’s no way around it: it’s tough out here for a wolf man.

But there was a brief window of time when werewolves were top dog (sorry, sorry). When arguably the three most inventive, fun, and thought-provoking werewolf movies ever made were released…all in the very same year.

So here’s a little tribute to 1981. The year my favorite nocturnal monster had its moment in the sun.

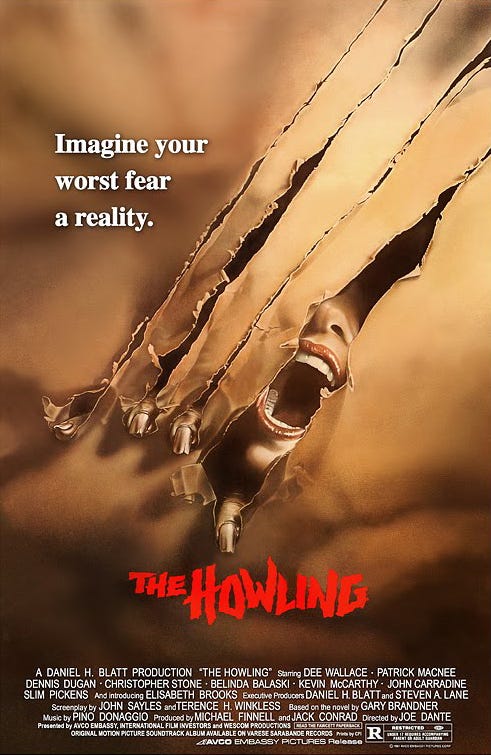

THE HOWLING

The first of 1981’s three werewolf classics was Joe Dante’s The Howling. Three years before Gremlins, the movie Dante is best known for, The Howling proved Dante’s talent for monster mayhem. The story follows Dee Wallace (a few years before she became America’s single mom in E.T.) as a TV journalist who represses a terrible brush with violence. A popular therapist suggests she take some time away at his rural therapeutic retreat called “The Colony.” Only problem is - you guessed it - this is a colony of werewolves.

The Howling has great early 80’s style and true scares, and while there is a undercurrent of thematic interest in sensationalist news media and the shallowness of pop-psychology, the real star of the show is special effects. Rick Baker was originally on the project but had to leave (to work on another film I’ll mention below) and handed the production off to Rob Bottin, who would later do some legendary work on John Carpenter’s The Thing. The wolves here are truly monstrous. Towering, sharp-eared, bipedal nightmares that bust through walls and tear through flesh like tissue paper (one thing I love about this monster is its variation…no two werewolves on this list look alike).

There’s a lot to love here, and The Howling has earned its place as a classic, but from here the wolves of 1981 only got better and smarter.

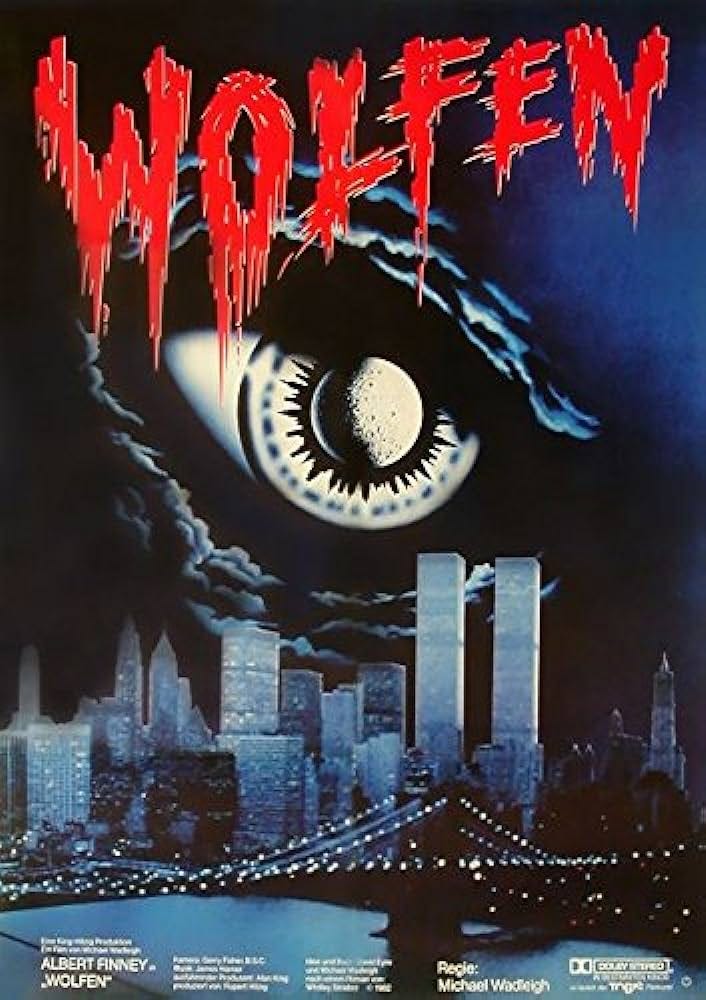

WOLFEN

Michael Wadleigh’s Wolfen isn’t your traditional werewolf movie. Or maybe it’s the most traditional. It doesn’t feature a classic transformation scene with elongating fingers and tufts of fur or a lumbering beast that stands upright and dashes between moonlit trees. What makes this under-appreciated movie a memorable and even vital entry in the genre is its conscientious exploration of werewolf mythology in a contemporary setting. Wolfen is ultimately a story about what we’ve done to the natural world, and what might happen if nature fought back.

Structured as a procedural crime thriller, Wolfen follows the great Albert Finney as Dewey Wilson, an NYPD detective investigating the killing of a wealthy real estate magnate and his wife in Battery Park. When more grizzly killings occur around a demolition site in The Bronx and in the dark tunnels of Central Park, two things become clear: this killer has a reason for killing, and this killer isn’t human. The investigation leads Wilson to a group of indigenous activists who tell him about a myth of a predator that, if threatened, will do whatever it takes to protect its stolen land.

It’s an incredible film if you like New York in midwinter, and has a host of wonderful character actors like Gregory Hines, Tom Noonan, and Edward James Olmos. What makes it stand apart is that it is a rare breed of conscious thriller that has plenty to say but pulls no punches when it comes to spilling blood. Wolfen uses the genre to explore what happens to a culture after generations of systemic subjugation and devastation and our arrogant, careless treatment of the natural world. The kind of thoughtful, committed, and stylish genre picture that raises the bar for the genre. This werewolf movie, more than any other, deserves a second life.

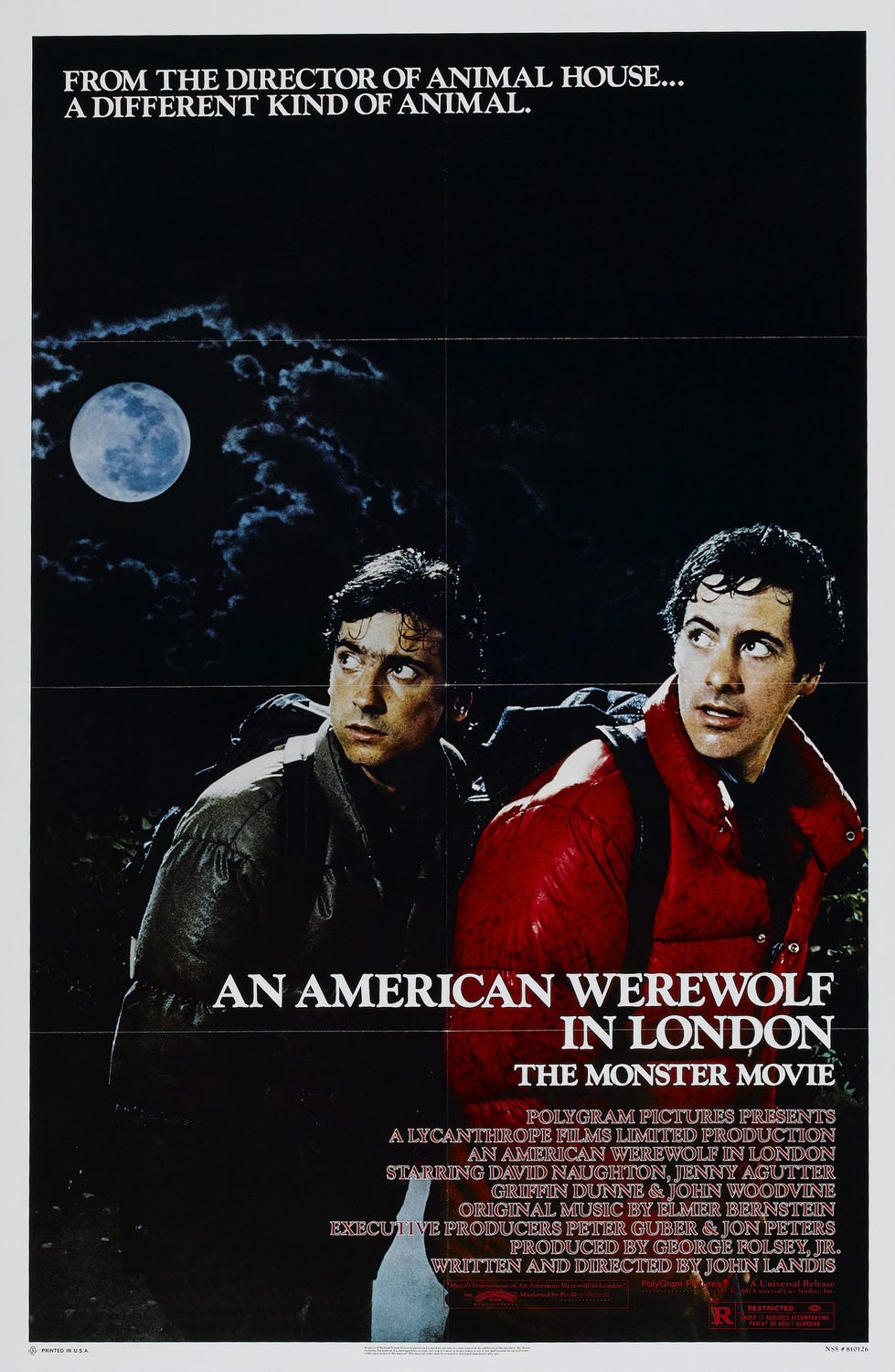

AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON

As far as werewolves on the big screen, it doesn’t get any better than this.

An American Werewolf in London, John Landis’ turn toward horror following the releases of Animal House and The Blues Brothers, really shouldn’t be as wonderful and layered as it is. But there is so much in this film - from the silly to the frightening to the oddly sublime - that makes it, for my money, the greatest werewolf movie ever made.

This film towers above the rest of the pack for its sense of fun, balance of tone, truly astonishing practical effects (Rick Baker’s work won this film the very first best makeup Oscar), deep bench of comedic actors including an appearance by Frank Oz, and its fundamental understanding of what the werewolf as a storytelling device can do best: explore the worst that resides in us, just beneath the surface.

In most werewolf movies, even those I’ve mentioned above, the thematic focus is on rage or lust or some repressed trauma, but to me this film seems to argue that the thing that makes us most monstrous is good old-fashioned selfishness. Our animalistic desire to look out for our own wellbeing above the wellbeing of others.

One of my favorite moments in this movie comes near the start when Griffin Dunne (giving an incredibly fun and increasingly unsettling performance) is attacked by an unseen beast on the fog-laden moors. David Naughten’s character - our supposed hero - does something that a film’s protagonist almost never does: he turns tail and runs. His friend screams behind him, being torn to shreds as he flees. Only after running for some time does he stop and realize what he’s done, and go back to help…dooming himself to the curse of the werewolf.

This reflexive action is entirely unheroic, and incredibly real. So real that it’s jarring to see in a horror comedy about tourists who turn into monsters. We don’t like our heroes to be cowards. We don’t want to see those unsavory parts of ourselves presented on screen. We want to believe that we wouldn’t run, that we would stay, fight, win…all of those things heroes do. But this isn’t that story. It’s a story of how we might very well doom those around us to death and suffering if it means we get to go on. A story of the casual cruelty we do in service of our own self-preservation.

I’m making the movie sound deep (which I think it kind of is) but mostly it's a whole lot of fun. There are wonderful comedic beats, some really exciting and unique sequences (including a dream sequence with machine-gun wielding werewolf nazis) and plays more like a twisted romantic comedy than a treatise on the rotten core of humanity. But that core is there. An American Werewolf in London is both a funhouse and a mirror. A strange, funny, ultimately tragic movie that proves there are more kinds of stories that can be told if we only let this particular monster out of the cage.

I’m not sure what was in the air back in 1981, but I’m glad this moment happened, even if nothing since has come close. I love all three of these films for their mix of dark fantasy and self reflection, the tendency of each to allow comedy and tragedy to coexist in surprising harmony.

It’s been 42 years (or 504 full moons) since the year of the wolf. I think it’s about time for a comeback.

Thanks for reading. Paid subscribers: please leave a comment with your favorite movie monster!