Here’s a question:

When is it okay to throw a grenade at a dog?

Now, you’re probably feeling a little put off by that question. You might even be saying to yourself: “what kind of person would ask that question, and how dare they, and furthermore forget this person altogether, because—honestly?—something is probably wrong with them and they obviously aren’t very nice so forget it, no way, bye.”

Fair enough.

I’ve had countless moments like this while watching films. Moments where I see something on my TV (or, preferably, on a big screen surrounded by other people) and I feel suddenly on guard. I’ve never walked out of a movie theater, but I have found myself watching something and deciding, sometimes based on a single word or shot: that’s it, I’m out.

But I think that is almost always a mistake. When I bump up against certain moments in films—moments that are particularly uncomfortable or strange— it is often because they are challenging my idea of the world and my ideas of what films can and should do. But my idea of the world is not the world. Our world, and the imagined worlds of films that reflect and reinterpret it, aren’t always comfortable places. The films that acknowledge this, directly or in odd and inventive ways, are (for me) so often the films that really stick. Sometimes a little bit of discomfort is just what it takes to make you fall right in love with a film. Those stories that invite us to examine and expand our ideas of what is right, permissible, or even possible are the films we keep coming back to, over and over again. The ones that really get under our skin.

These stories usually don’t tell us everything right up front. They aren’t concerned with making us feel at ease, or impressing upon us how nice or friendly they are, or that we are safe in their hands. These stories are instead interested in showing us something. Something that invites us to confront questions that might have otherwise been avoided or might never have occurred to us unless provoked. Questions like: when is the totally-not-okay not only good, but necessary?

What are the circumstances under which you might look at men in a helicopter chucking explosives at an innocent looking dog and think to yourself:

Yes. Do it. Get that dog.

John Carpenter’s “The Thing” is my favorite film. Well, it’s one of several in a rotating (and slowly growing) group of films that I could reasonably name as my favorite. But, seeing as October has just begun, and that October is that beautiful time of year when the temperature drops and the lights outside dim to the perfect level where you can’t help but curl up on a couch with a blanket (and maybe a dog) and turn on a movie that puts you on edge…let’s call it my favorite film.

It's also a film that, in its first few minutes, shows men literally tossing grenades at a sled dog running through fields of clean, unblemished snow. This dog—as far as we know—has never done anything to anyone and is simply up here in this arctic landscape minding his own dog-business.

So, what is this opening doing? Is it just trying to upset you? Or is it an invitation? An open door, welcoming you inside to show you things you’ve never seen, or maybe were just avoiding looking at directly. Things that might disturb (challenge) your comfortable (default) sense of of the world. All you have to do is not turn away. Accept the invitation.

So: When is it okay to throw a grenade at a dog?

The answer:

When the dog isn’t a dog at all, but something else entirely.

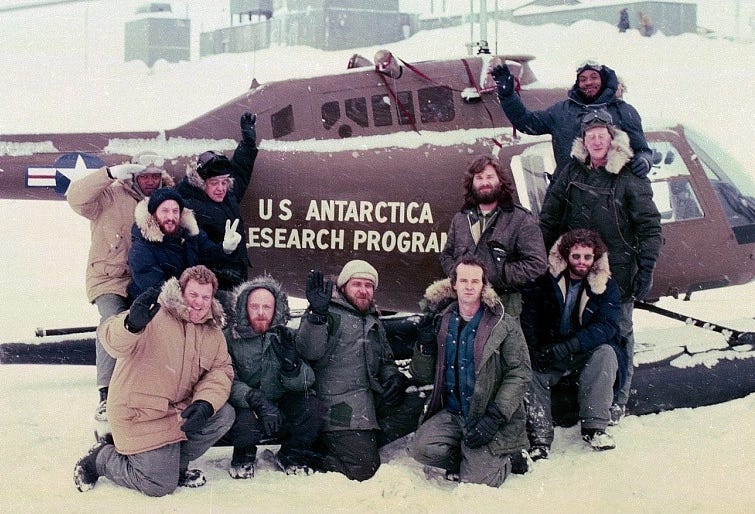

“The Thing” was adapted from John W Campbell’s 1938 novella “Who Goes There?” (he wrote it under the pen name “Don A, Stuart,” which he borrowed from his wife…Dona Stuart). The story follows a group of Americans at an arctic research base who discover a terror from outer space that can consume and perfectly imitate other life forms. It’s a perfect narrative machine for exploring ideas of paranoia, masculinity, our fragile sense of self-hood, and how we behave in the face of things we don’t fully understand. It was previously adapted by Howard Hawks in 1951’s “The Thing From Another World,” a movie that, while entertaining, wasn’t able to accomplish the feat that Carpenter’s film is perhaps most notable for: representing this shape-shifting terror on screen.

For nightmarish visuals, you simply cannot beat “The Thing.” The practical effects, designed and realized by Rob Bottin (who was only 22 at the time and lived on the studio lot and worked himself into a wicked case of double pneumonia), are astonishing; sometimes terrifying, sometimes hilariously outlandish, and always overflowing with creative ingenuity. That, and goo. Lots and lots of goo.

For a story this full of guts, gore, dynamite, and flame throwers, “The Thing” is surprisingly patient, meditative, and even slow at times. There are long stretches of silence (punctured by Ennio Morricone’s menacing, heartbeat-like synth score) where nothing much happens at all. We see empty halls, men sitting quietly, snow accumulating. There is an unsettling quality to these moments that rivals the eruptions of violence, when the tension ratchets tighter and tighter, and Carpenter shows us that he is attempting to do much more than just gross us out.

There is one moment like this in the film that I love more than any other:

The fleeing dog, who we are relived has escaped those bad men with grenades, wanders the vacant halls of the Americans’ sleeping quarters. It comes to an open door. Inside we see the shadow of a man, alone. Who this man is, we don’t know, and never discover.* The dog waits at the door. Watching. Contemplative. After a moment, it steps inside, and the shadow of the man turns.

The scene ends.

So why do I love this moment? It’s a quiet moment, sure. But it’s also quietly explosive. A dog coming to visit a man in his bedroom shouldn’t be frightening, and yet you feel and acute sense of disquiet. You’re suddenly on high alert. Unsure of what you’d previously taken for granted: that this dog is just a dog. What should be a perfectly normal encounter curdles to something sinister, and in that moment the whole story shifts. You begin to think a thought that might surprise you:

Maybe those guys in the helicopter were on to something.

And what an exciting thought that is. To find yourself suddenly considering a perspective that was, only a few minutes ago, inconceivable, and even offensive to your wholesome, dog-loving principles.

Of course, it’s not long after this that all hell breaks loose. That this self-same dog’s face peels open—blossoms in an eruption of tentacles and gore—and we learn that it is not a dog at all but something pretending to be a dog. The dog was only a Trojan Horse, a form that has allowed it to be welcomed in among these men. Men who are, as the film’s tagline proclaims, “the warmest place to hide.”

And of course, this tells the viewer something else about this villainous shapeshifting monster from out of space: it’s not just a raging pile of gelatinous goop, it’s also pretty clever. Maybe this thing, having spent a little time among mankind, knows precisely that a dog is the best form for it to take, because after all, who in their right mind would harm a dog?

No one. Not you, certainly.

And that’s why “The Thing” has you, right where it wants you. Because there is a part of you that bristles at that first scene. That wants that dog to evade those explosions. Because you are human. And being human is what compels you to open the door and let it inside.

The delightful discomfort of this whole shooting-at-the-dog business—not to mention everything that follows—didn’t sit well with audiences at the time of the film’s release. “The Thing” is now widely considered one of the most impressive and unique films in the horror genre, and arguably Carpenter’s masterpiece, but was a commercial and critical bomb that nearly derailed the director’s career.

One story (which I love but can’t confirm) tells of an early screening where Carpenter was asked about the film’s ambiguous ending in which two men are left among the burning wreckage, each unsure if the other is man or monster. The crowd wanted a straight answer. Who’s a thing, and who’s human? Carpenter encouraged the audience to use their imaginations, which prompted someone to audibly groan and say: “Oh, I hate that.”

There was such resistance to the film’s nihilism, its nightmarish imagery, its openness to interpretation that one critic dubbed it: “Instant junk.” Another: “The quintessential moron movie of the 80’s.” Another: “The most hated film of all time.”

Now—just over 40 years later—you’d be hard-pressed to find a list of the greatest horror and science fiction films that doesn’t include “The Thing,” In fact, it’s often right near the top. I think that’s because, just like the monster in the film, the core ideas of this film don’t always scream right in your face. They also take their time. Like insidious alien spores, they grow on you.

I remember the very first time I saw this film. It was in a basement with a bunch of other teenage boys (perfect targets) who had heard about this strange, gross-out movie. I remember the feeling of sitting there, seeing things I’d never seen. Laughing, gasping, and becoming acutely aware that lines I didn’t even know were there were being revealed to me and almost at the same moment crossed…and that I was enjoying it. It wasn’t just the monster on the screen that felt alive, it was me, my sense of things, waking up to what had been lurking too deep or too far out to see.

Since then, I’ve watched “The Thing” more times than I can count…but a lot of those watches are memorable because of the people I’ve shared it with and the circumstances that seem to call the film to mind. I always love showing it to new friends who haven’t seen it, and I cherish the conversations that inevitably follow. I’ve also watched this movie alone late at night after visiting a family member in the hospital, unable to sleep, feeling uncertain of my place in the world and awake to my own fear. I watched it several times while isolating from the rest of the world during a global pandemic, feeling disconnected like the men in the arctic outpost. I watch it to reconnect with wonder, or to face down a feeling that frightens me. I watch it for its dazzling effects, it’s doom-drenched score. I watch it for its potent themes of mistrust and how easily we lose our grip on one another and ourselves. I watch it for Kurt Russel’s big hat…. and now it’s a part of me. A weird, wonderful thing living deep inside my skin. A disturbance and a comfort; both at once.

And it all begins with that dog, running for its life through the snow.

So now, about once a year or so, I find myself in the same position: sitting on my couch, my dog (who I love dearly) by my side, watching those brave men in the helicopter do their best to stop that dog (who is not a dog) before it can hurt that nice looking group of Americans in parkas, and I think to myself: If only they’d aimed a little better, all this could have been avoided.

…But then the story might have ended right there.

On second thought:

Run, dog. Run.

What a great read