Angle On: The Shapeshifter

The Many Faces of Tom Ripley

I’ve been spending a lot of time with an old friend of mine. Some think of him as a cold-eyed predator, his crimes many and unforgivable. Others pity him and identify with his predicaments, if not his methods. Many even find themselves, against their better moral judgment, rooting for him. He has gone by many names, and has worn many faces, but we know him best simply as Tom.

Tom Ripley was born in 1955 when Patricia Highsmith published her best-selling fourth novel, The Talented Mr. Ripley. Her previous works included Strangers on a Train, her debut, which was adapted by Alfred Hitchcock only one year after its publication, and The Price of Salt, which was written under a pen name and later adapted by Todd Haynes with the title Carol. Highsmith, who by most accounts was an enigmatic if recalcitrant figure, had a knack for telling dangerous and thrilling stories from the start; the kinds of stories that made her novels all-but-inevitable fodder for the big screen.

A queer woman writing pulpy yet elegantly crafted crime stories in an era dominated by cool-as-hell hardcase gumshoes (no offense to my friends Chandler and Hammett) Highsmith is one of those singular literary figures whose work seems, in retrospect, like a kind of miracle. The characters she conjured managed to be both truly diabolic and yet entirely worthy of empathy, and the scenarios she placed them in were meticulously engineered to create gripping suspense. It’s generally agreed that nowhere in her work were these dangerous and enticing elements better distilled than in the character she kept alive across 5 books and as many decades.

Tom Ripley has been portrayed on screen with steady consistency since the 1960s, in five movies, two television series, and one BBC Radio Four program (it’s possible I’m missing something here…Tom does have a way of sneaking past you) making him among the most enduring characters in cinema. To put it in perspective, his first on screen appearance predates the first James Bond Movie, Dr. No, and he has been played by the same number of actors as old 007. While these appearances are almost entirely stand-alone, Ripley has managed to cultivate a kind of shadow franchise that has endured for over half a century. His twisted conception of success and the American dream, his relentless pursuit of an identity he can feel at home within, and most of all his ability to wriggle out of pretty much any sticky situation, remains as relevant today as it was when Highsmith first gave him his name.

This enduring relevance is evidenced by the recent release of Ripley, a new highly cinematic Netflix series that sees Highsmith's first book adapted yet again, this time with a new Tom at its center. This resurfacing of the dastardly old shapeshifter seems like the perfect opportunity to look back on all of the renditions of Ripley, their differences and striking similarities, to trace how this chameleon has managed to stay fixed in our cultural minds for nearly 70 years and counting.

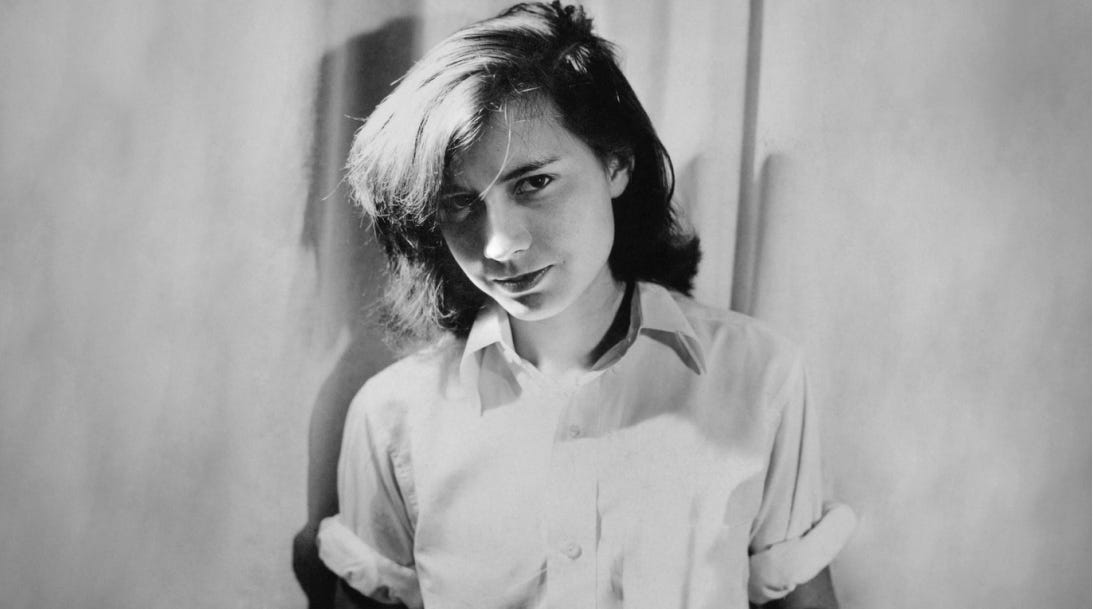

Alain Delon - Purple Noon (1960, Dir. René Clement)

The first on-screen incarnation of Tom Ripley was French actor Alain Delon. Delon, then only 25, was early in his career when the role came along. He would later solidify his star as an accomplished actor with a steely demeanor and knack for conveying interiority—not to mention a bonafide sex symbol—with films like L’eclisse (1962), Le Samourai (1967), and La Piscine (1969). His arresting good looks might be the only count against him as a fitting Tom Ripley (let’s be real, it would be hard not to notice this guy in a crowd), but in most regards I have to agree with Highsmith when she called Delon’s portrayal of her character “excellent.”

If you possessed no prior knowledge of the character (and many people didn’t, as Purple Noon was released only a few years after Highsmith’s novel), it might come as a surprise when he emerges as a killer. This story begins in medias res, cutting out explanations of how Tom came to find himself hanging out with a guy named Dickie Greenleaf (named Phillipe in this version) and living it up in the bars and beaches and boat decks of Southern Italy (in the book Tom is hired by Dickie’s father, a wealthy man who mistakes Tom for a friend of Dickie’s, to go and find his son and bring him home). It’s an odd choice, but allows the film to do something kind of remarkable: to let us get to know the fake Tom before the real one is revealed.

Delon presents us with the most outright sinister portrayal of Tom Ripley. Where others seek to imbue the character with qualities that either delight our sense of taboo or beg our sympathy, Delon merely seems to have his finger on a single switch: this way on (friendly, charming, startlingly handsome) this way off (utter and complete blankness). While other Toms might be notable for their knack for deception or desperate self-preservation, it is Delon’s stillness that makes his Ripley memorable. His unnerving and effective vacancy render this Ripley as a conniving and psychopathic killer, through and through. More predatory than the others, and far less sympathetic. Delon betrays traces of panic and desire throughout, but mostly what this actor gives us—intentionally end effectively—is an empty shell. Though, as shells go, he’s pretty easy on the eyes.

It was 17 years before Ripley appeared again on screen, this time in a radically different form.

Dennis Hopper - The American Friend (1977, Dir. Wim Wenders)

Adapted mostly from Highsmith’s “Ripley’s Game,” though containing plot elements from “Ripley Underground” (both novels in what is often called the “Ripliad”) The American Friend finds Tom Ripley out for something like revenge, rather than transformation. But what makes this film stand out is what a wildly different Tom this Tom turns out to be.

Director Wim Wenders leans away from the sun-drenched glamour of Purple Noon, imbuing Highsmith’s world with his own deeply romantic yet broodingly patient style (evident in films like Paris, Texas as well as Wings of Desire and his new film Perfect Days). Ripley, dealing art forgeries in Germany, is insulted by a frame-maker, who he discovers is terminally ill. As payback for this minor slight, Ripley has the dying man conned into acting as a hit man for some criminal friends. What follows is a truly gripping—sometimes funny, sometimes grim—story that follows Ripley and the dying man (played by the remarkable Bruno Ganz) as they shift from adversaries to unlikely friends.

Dennis Hopper’s Ripley is not the dead-eyed killer that Delon gave us, nor is he all that similar to any Ripley that would follow. In fact, Hopper’s take on the character might throw the viewer at first glance. He seems far less concerned with outward appearance and cultivating an air of elegance, and mostly wears a large cowboy hat and coveralls. His eccentricities and unpredictability are what define him. He is erratic, impulsive, yet no less tactful when it comes to executing schemes or getting the best of a bad situation (especially during one memorable scene where almost every character find themselves aboard the same speeding train).

There are scenes where he is manic, others where he is sorrowful. Moments where he shows tenderness, and others where his rage rises to the surface. By the end, Hopper gets to play every side of Ripley. A man who you don’t want to cross, who will bend the world to make you pay for a slight word against him, but also someone who desires, more than anything, connection. Tom might bludgeon those he calls friends from time to time, but as it turns out in The American Friend, Tom might just be the best person to have on your side in a tight spot…even if he is the one who put you in the spot to begin with.

While Hopper’s Ripley may not be my favorite of the bunch, the film is. It’s an under appreciated gem, one that didn’t make nearly the impact that the next Ripley film did over 20 years later.

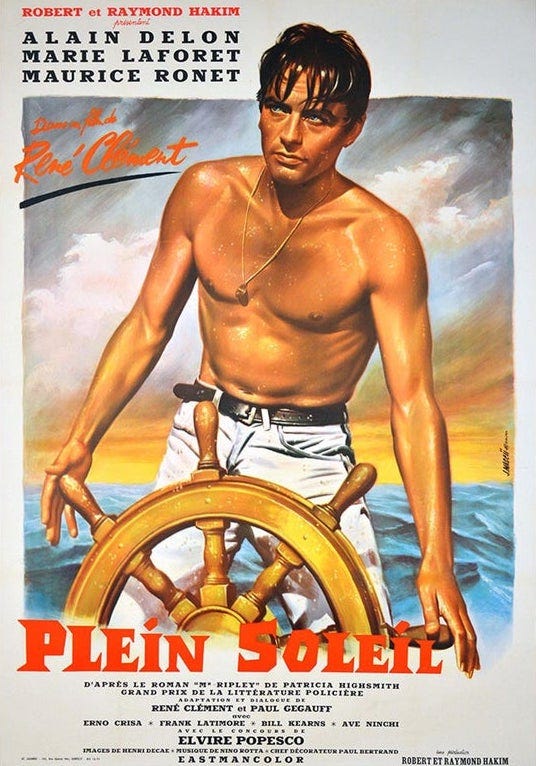

Matt Damon - The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999, Dir. Anthony Minghella)

Perhaps the most well known Tom Ripley is Matt Damon’s 1999 take on the character in a same name adaptation of Highsmith’s first Ripley book. A late nineties feast of bright colors and young rising stars, this film is a more faithful adaptation, even to the point of being a little on the nose. Where the previous Ripleys, though distinct from one another, were both largely cyphers, this Ripley is a bit more…exposed. Damon, in one of his best performances, brings dynamics and interiority to the role, but also comes right out and says things that make the character’s duplicitous nature and psychologically complex motives searingly clear, and even a little reductive: “I’d rather be a fake somebody than a real nobody.”

The result is a totally accessible Hollywood thriller, that also, somewhat miraculously, feels layered and dangerous in ways that studio movies with big stars rarely do. This may be due to the fact that while all of the dark twists and turns of Highsmith’s work are here, this is the first of Ripley’s on screen manifestations to do what the novel does so well, primarily by way of its first person POV. That is: allow the audience to feel real, palpable sympathy for this killer.

Damon’s Ripley is without a doubt the most outwardly pitiable of the bunch. He is self-conscious from jump, often looks wounded or hopeful (a far cry from the shark-like vacancy of Delon) and his visible desire, more than anything, is what makes this performance unique. He is defined less by his murderous inclinations or survival instincts than by is desperation to be included, to be one of what he feels are the beautiful people—which in this case does of course mean outward beauty, in the form of Gwyneth Paltrow and a particularly magnetic Jude Law as Dickie—but even more so the beauty that comes with effortless wealth. In Dickie’s case this wealth is inherited, and something he claims to resent, wishing instead that he were a struggling artist (Dickie is either an aspiring jazz musician or a painter, depending on the film). For Tom, this wealth feels within arms reach, but also totally beyond him. The only way to become what he admires, he discovers, is to destroy it and replace it. Ripley ‘99 does a bang-up job portraying these scenes, even to the point where its script starts to feel like overstatement.

This adaptation doesn’t shy away from something that Purple Noon, for all its sensuousness, mostly skirts. On top of being a ripping good crime yarn, The Talented Mr. Ripley is imbued with palpable themes of queer desire. Highsmith, keenly aware of the era in which she nevertheless deftly explored this topic, has a knack for subtlety, but it's still hard to miss that Tom’s sexual identity and his feelings toward the people around, especially Dickie, is a major part of how and why the story unfolds. This film, more than any other here listed, contends with these themes and represents them on screen in ways that even the most recent adaptation does not. Ultimately, the scenes between Dickie and Tom are the best of the film (oh, and that one Philip Seymour Hoffman scene), even to the point of diminishing what follows. The tension between the two is so compelling that the violence that eventually occurs hits us (and Dickie, ha ha) much harder for it. It’s perhaps the ultimate lesson of this version that the people Ripley admires, destroys, and becomes, are at least as important as the man himself.

The Talented Mr. Ripley is a bit of a relic of its era (those opening credits, so nineties), but there are also aspects of its execution that feel totally timeless. It was a hit then, and seems only to have grown in estimation with the decades that followed. It’s a shame, then, that once Ripley really had some steam, the films that came next didn’t make nearly as big a splash.

John Malkovich - Ripley’s Game (2002, Dir. Liliana Cavani) & Barry Pepper - Ripley Underground (2005, Dir. Roger Spottiswoode)

I’m going to glide through these two Ripley’s quickly because they are, I’m sorry to say, not really worth dwelling on. Two perfectly serviceable performances in movies that haven’t lasted in our cultural imagination, and when you watch even a little of each film, it’s not hard to see why.

John Malkovich portrayed Tom in Ripley’s Game (an adaptation of the novel of the same name, which was also the primary source material for the much better The American Friend) and Barry Pepper took the role in Ripley Underground, an adaptation of the second Ripley book (some small parts of which were also repurposed in The American Friend….just watch The American Friend).

Malkovich’s take on the role is subsumed by his general love-it-or-hate-it (or just tolerate it) Malkovich-iness, which does works in certain ways. His erudite mannerisms and stagey over-pronunciations feel distinctly performative, which in a meta sense works for Ripley, a man constantly performing. And yet he doesn’t do all that much new or compelling with the role, especially when compared to the unexpected and singular work that Hopper turned in with similar material. Barry Pepper, always a reliable supporting player (The Green Mile, Saving Private Ryan, etc) struggles in the center of a psychological drama that doesn’t seem to have all that much to say, though that might have less to do with Pepper’s efforts than the fact that this Ripley story, of the three translated to screen, is the least interesting, and the direction here ends up feeling more soap opera than subversive.

What’s most interesting about these two films, which occurred in quick succession, is the fact that Ripley then vanished from our screens for nearly 20 years.

Then, just this month, he returned in ways that seem both bold and new, yet also stripped down to the core elements.

Andrew Scott - Ripley (2024, Dr. Steven Zaillian)

Simply titled Ripley, the newest take on the character is not a film at all but a series (I don’t intend to write much about TV here, but in Tom’s case I’ll make an exception). Steven Zaillian—most known for writing films like Schindler’s List, The Irishman, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, etc.— has crafted this stark and notably elongated version of the story, but that doesn’t mean there is more here than we’ve gotten in the past. The story, like its title, has been stripped of a whole lot, from characters to plot points to color. The result is a spare and patient and striking return, once again, to Ripley’s inaugural tale.

This time our Ripley is Irish actor Andrew Scott (née Hot Priest, one-time Moriarty, you know him). Andrew Scott is a unique and exciting actor that you’ve probably seen in something and more than likely loved in whatever you saw him in. He is winsome and sharp, more than capable of playing villains, but with an equal capacity for being charming. In certain roles, especially last year’s All of Us Strangers, Scott has shown an ability to convey an incredible depth of feeling through quiet, and largely internal performances. He is also (like Tom) a gay man, though this show seems far less interested in sexuality than the ‘99 film, for instance. These themes are not absent, but neither are they a central concern of the show, which notably lacks certain elements of the story including what need only be referred to as “the bathtub scene.” About the only reasonable criticism one might lob at this casting is that Scott is a bit long in the tooth for this part (Ripley is about 25 in Highsmith’s book, while Scott is 47). Though Ripley and the people around him are largely defined by their position on the cusp between youth and adulthood, and Tom in particular seems absorbed with youthful aspirations, this age discrepancy feels like a minor issue because, in virtually every other sense, Scott feels perfect for this role.

Many viewers who know Scott’s work will feel this way going in, and may be struck by something when she series begins: Scott’s portrayal of Ripley is noticeably, emphatically unshowy. He lives in a crappy apartment, pulls off unexciting white collar crimes, and goes through these motions the way most of do our taxes. If you’re looking for driving, repulsive energy, this show may not be for you. It is a much slower, almost forensic take on the story. One that, despite its elevated appearance, seems to care most about the logistics of murder. The ink-soaked paper and blood-soaked rags that are Tom’s means of survival.

Ripley unfolds like a protracted autopsy of events and their consequences over 8 episodes, almost all of them an hour long (making it in total four times as long as the last adaptation of this book). That this show contains far fewer plot points than the ‘99 adaptation is startling at first ( for instance the character of Meredith Logue, played by Cate Blanchett in the ‘99 film, is totally scrubbed out, as are several other major players) but it quickly becomes clear, and then abundantly so in the show’s third episode, that Ripley is primarily interested in portraying the bitter banality of Tom’s crimes. Moments of violence are over in a second, and then comes the work. Work which this Ripley is good at, but goes about with a lack of either enthusiasm or despair (where Damon’s Ripley weeps, Scott’s Ripley merely sighs).

This Ripley feels, more than anything, tired. Tired of being who he is, or isn’t. But determined, nonetheless, to press on. And it works, especially as Tom’s crimes mount and those seeking him press closer. What keeps Ripley from feeling like a plodding if beautifully photographed snuff-film followed by lengthy clean up (repeat as needed) is Scott, in whose capable hands this tight-lipped Tom comes to feel, over the course of these hours, undeniably human.

Scott brings a quiet but hefty dose of heart and soul (if Ripley can be said to have those things, and I say he does) to this otherwise cruel and dour world. He also affords us, the viewers, the opportunity to see something crucial about Tom and the world in which he moves. Once he kills, once he sheds his own name for another’s name and all that comes with it, the colors don’t suddenly flood in. There is no Wizard of Oz moment in which Tom’s life suddenly becomes vibrant and joyous and carefree. It remains as it has been. It remains lacking some essential vitality. Murder and transformation may be the things for which Ripley is known, and to some degree adored, but they do not win him what he seeks. They only get him more of the same.

At the end of this series (and at the end of almost all of these films) Tom’s search for comfort and fulfillment and companionship and selfhood and whatever else he’s searching for continues.

Having spent so much time with Tom(s) I can’t help but feel there is something about this character that feels fundamental to the American psyche. Then and now. He is the inverse of the bold and brash American heroes that so often light up our screens. In this culture we tend to admire those who stop at nothing, but Ripley’s tenacity is less a virtue than a source of uncanny terror. Uncanny in the sense that it is familiar. Because his desire is our desire. We want to be included, to rise to the top, to have it all, to be admired, adored, accepted. We compromise ourselves daily, in a hundred small ways, to achieve proximity to those fragile desires. Ripley just goes…a little further. His methods may be ruthless, and while they too only manage provide a small taste of a “better” life, it never lasts long. After a while he’s back again. New city, new clothes, new time, new face, same name.

Purple Noon and The American Friend are both streaming on the Criterion Channel and are available on Criterion blu-ray. The Talented Mr. Ripley is streaming on Paramount+. Ripley’s Game and Ripley Underground are available to rent. Ripley is streaming on Netflix.