Angle On: The Infinite Diner

The Recurring Entanglement of Eternal Sunshine of The Spotless Mind

When I was growing up, my family would take yearly trips out to Montauk. If you know the town, you also know that the place has transitioned from a family friendly and relatively working class alternative to the Hamptons to just another appendage of the Hamptons. While the slow invasion of posh brand name storefronts and white land rovers hasn’t rendered the place unrecognizable, things certainly have changed. The motel we used to frequent is still there (though it’s had several renovations and new coats of paint to go with its updated rates) and a few landmark establishments have survived the steady bougie-fication, but one place that is gone for good is The Plaza Restaurant. An archetypal diner my family and I would visit for beautifully basic breakfast fare. The kind of place with warm ketchup bottles on the table and menus covered in plastic to protect from a sun-drunk family of five’s inevitable spills.

When I went back to Montauk for the first time with my partner (ten years ago this summer) the diner had been replaced with a startlingly sterile fish taco joint. I guess that didn’t last, because last time I was there the spot was vacant, though the bank next store was alive and well. I’m far away from Montauk today, but a quick search tells me that the location is now home to an Italian restaurant with a menu that features a 20 dollar caesar salad and a 100 dollar bottle of wine; a far cry from the place that used to sling leaning towers of pancakes and bottomless mugs of burnt coffee. This once beloved home to single-use creamer cups and vinyl booths that would stick to my sunburnt thighs exist now only in memory. Oh, and also in a film about memory.

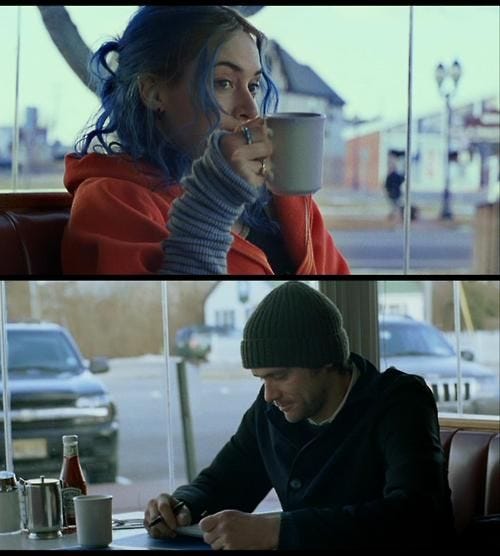

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind opens with Joel Barish taking the LIRR out to Montauk, following an impulse he doesn't fully understand, on Valentine’s Day, 2004. It’s now exactly 20 years later. This film is 20 years older (and, apparently, so am I). After a short walk on an inhospitable beach, Joel settles into a booth at this very same diner. Clementine is there too, pouring gin into her mug. They might have been there before, together or alone. They might be there again. I know their story, and I know that place, and right then it doesn’t matter what’s gone. I’m just glad to be back.

This film has been on my mind for a number of reasons (one being it’s inclusion on a new Criterion Channel collection dubbed “Interdimensional Romance,” which features other great genre-inflected films like After Life, Your Name, Defending Your Life, and both versions of Solaris). Even if there were no anniversary, I would have put this on sooner of later. It always seems to come to mind around this time of year, when beaches turn windy and cold. I know it’s the same for a lot of people, especially of a certain generation. We’re drawn back to this story for reasons we feel but can’t quite name.

What captured most of us about Eternal Sunshine initially, I suspect, is its unique and undeniably off-beat style. The visual language of this film, brought to life by Michel Gondry, would be enough to charm anyone, and worked like gangbusters on a generation of emo inclined millenial teens like yours truly. The imagery is probably what first comes to mind when you think of this film: the chases down maze-like halls of memory, the sudden erasure of book spines and commuters, the forced perspective of the childhood scenes, which evoke more fluently the feeling of smallness than every Ant-Man movie combined.

The delightfully street-level science fiction concept of targeted and intentional memory loss is still a great idea and resonant conversation starter, but what jumps out to me on my umpteenth rewatch of this film is not the high concept or the fanciful execution (well, not only that). What really gets its hooks in me is this story’s elegiacally optimistic view on the messy everyday love that exists between two people. Love that is proven doomed, but love that is chosen anyway, over and over.

That this strange film works as well as it does is a credit to writer Charlie Kaufman’s unique storytelling style and perspective. The film’s structure alone is something to behold. Its wild temporal shifts yet consistent narrative logic would make Christopher Nolan acolytes swoon, but it isn’t showy about it. The real-time discovery of when you are and how that inflects all that came before makes the story feel both intimate and vast in a way that most films never achieve. The shape of this story makes you feel as though you are experiencing the full spectrum of a relationship, not being presented with a facsimile of one. It’s the sort of movie that you could convert into charts and timelines if you wanted…but you don’t want to, because you’re too busy feeling to stop and think. It’s that rare movie that doesn’t draw attention to how smartly it is designed. It just moves, and you can’t help but move with it.

But none of this would matter if not for Eternal Sunshine’s best magic trick: it’s cast. It’s easy to forget how wonderful Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet are in this movie, in particular when you place them in the context of their careers up to that point.

It’s almost rote to applaud comedians for taking a dramatic turn, but this one is a truly remarkable about-face for Carrey. In the 90s, there was no more outlandish or wildly electric comedic leading man. As Joel, Carrey not only tamps that familiar bombast down with ease, but fully embodies a person who is all but incapable of accessing the joyful freedom its actor is celebrated for. Watching this performance feels like witnessing someone truly unobserved. A person most comfortable in hiding, and who turns vindictive when his thin allowance for vulnerability gets him hurt. That you don’t emerge from this repelled by the vengeful sad sack Joel is is a testament to Carrey’s ability. He’s likable and magnetic, even stripped of all his usual tricks.

Even more impressive to me is Winslet’s performance as Clementine. A deft subversion of the “manic pixie dream girl” trope before it even had a name. Known almost exclusively for period pieces at the time (please seek out Heavenly Creatures) it was a little unthinkable that Winslet was to portray a modern woman, let alone an extroverted alcoholic (an aspect of her character that was lost on me while young, but now feels central to the narrative) from Rockville Center. Yet she brings to this role a layered desperation that is almost nonexistent elsewhere in the genre, especially where the objects of male affection are concerned. Behind every bit of self-mythologizing and evasive hair color re-dye is a palpably real person. One whose exuberance turns from enthralling to exhausting in the eyes of her partner. You can feel what a painful thing that must be for her in the spaces between her words, to go from worshiped to resented merely for being who she is. I suspect that level of depth is only possible with an actor of Winslet’s caliber and is a direct result of her input on the character from the production’s earliest stages.

And I’m not done, because this film has a frankly astounding supporting cast. Mark Ruffalo is here conjuring a strangely wounded proto-tech-hipster Elvis Costello. Kirsten Dunst is bringing her usual dose of dynamism to what could have easily been a trite side character in lesser hands. Elijah Wood, straight off of playing heroic cutie-pie legend Frodo Baggins, is perfectly slimy as a thickly side-burned creep using stolen artifacts as a crowbar into Clementine’s heart. Even the most minor roles are elevated by the likes of Jane Adams (an all time secret weapon character actor), and nothing in this film makes me laugh quite like David Cross saying “I am making a birdhouse.”

But the person I’m watching closest this time around is Tom Wilkinson, who sadly died in late December of last year. You’ve seen his face, whether here or in films like Michael Clayton, Batman Begins, Rush Hour, Shakespeare In Love, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Sense And Sensibility, In The Bedroom…the list goes on. His role in this film, as the pioneer of the memory-erasing tech (burdened with the lion’s share of expository dialogue) could have been something thin and unmemorable. He could have been maniacal and manipulative, dispassionate or even cruel, or just a plain old plot device. But Wilkinson’s performance is instead dominated by an unmistakable air of meloncholy. This is a guy who doesn’t just profit from regret, he knows it well. Where Joel and Clem arrive to him in fits of passion, erasing one another out of pain and spite, Wilkinson never feels anything but patient and strangely understanding. We learn, in the course of the film, that his experience with the procedure is more personal, but even with the revelation of his misdeeds he plays the character with humanity. Not the mad scientist but the sad scientist. He too is a victim of, abuser of, and general sucker for love.

In a world inhabited by such humane and richly realized characters, it’s clear that no one is safe from heartbreak, and no one particularly wants to be. Because to love is to risk heartbreak, willingly and recursively. To know the possibility (guarantee) of some pain down the road, but to say okay anyway. That this film says all that as uniquely and as clearly as it does was without falling into a boiling hot vat of cheese remains a pretty wonderful thing.

I sometimes wonder if I’ll throw Eternal Sunshine on one of these days and find its perspective and approach somehow too juvenile, too sad or too love drunk or too…something. I thought that might happen this time around. But it still proves to be effective and inimitable, situated at a strange intersection of oddball sci fi and earnest romance and black comedy and depressive drama. None of these tones step on each other’s toes but instead come together perfectly like a plate with too many different kinds of food. An unlikely scramble that produces a craving only it can satisfy.

I don’t know about you, but I’m of two minds about this holiday. On the one hand, I believe Valentine’s Day is a transparently capitalist contrivance to get us to buy singing gift cards and heart-shaped confections, to spend money on food and flowers in place of other perhaps more meaningful gestures. But it’s also a welcome excuse to take a look at the love in your life and maybe appreciate it a little more clearly and directly. To seed an ounce of intention into the romantic position you find yourself in, whatever it may be. And maybe that’s why Eternal Sunshine feels like the best film for this particular day, 20 years on. A film that so articulately declares its perspective on love as something burdensome, intoxicating, destructive, redeeming, and stubbornly, wonderfully persistent.