Angle On: One Of A Kind (Part II)

The Monsters We (Re)Create in "Carrie" (1976)

Happy Halloween.

According to several sources, Beetlejuice costumes are in this year. That’s the power of media. A sequel arrives, and just like that the miniature ghost with the most is ringing your doorbell. But open your door this halloween and among the many Barbies still hanging around from last year, as well as enduring franchise masks like Spider-men and the indelible minions, you’ll also probably see vampires, werewolves, ghosts, and zombies. Costume trends come and go, but some monsters stick around.

We’re all familiar with certain monsters from myth, whose imposing size and stature have gone a little out of fashion (our modern minds are more fixated on the threat of unresolved trauma than, say, tentacles), but most of us still know a cyclops when we see one. Or a dragon. Though we might not fear these creatures as people once did, we can understand the roles they play in the stories we have told and retold: they are there for the hero to kill.

But it’s also known, that such monsters were already hanging around for a long, long time before anyone bothered to write them down; giving those stories shapes that have now become second nature.

Take Grendel, for example, from Beowulf. Not the oldest story, but one of the most compelling and complete. If someone made you read it back in school, there was a good reason, though you might not have appreciated it at the time. The plot is simple, and familiar: a village is under attack from a monster, who visits night after night (that’s Grendel) and they need a hero (that’s Beowulf) to come and do…what heroes do. We’ve been retelling variations of this over and over, not to mention directly adapting them (go ahead and skip the Zemeckis version).

Tolkien (yes, that Tolkien) said of Beowulf:

…the old tale [Beowulf] was not first told or invented by this poet. So much is clear from investigation of the folk-tale analogues. Even the legendary association of the Scylding court with a marauding monster, and with the arrival from abroad of a champion and deliverer was probably already old. The plot was not the poet's; and though he has infused feeling and significance into its crude material, that plot was not a perfect vehicle of the theme or themes that came to hidden life in the poet's mind as he worked upon it. Not an unusual event in literature.

Different iterations of Grendel continue to run amok, but how are new monsters made? Now that giants and fire-breathing serpents have become sort of been-there-done-that, what new forms can they take?

They might just come to look more and more like us.

There’s a famous, possibly apocryphal, story about how Stephen King’s first published novel, Carrie, came to be. The story goes: he wrote the opening scene, in which Carrie White gets her first period in the school locker room and is taunted maliciously by her classmates. Carrie does not know what is happening to her body, has not been forewarned, and therefore is terrified that she is dying while the other girls laugh and pelt her with tampons. It’s a harrowing scene, one that gets at so many deep fears….but still, King crumpled up these pages and threw them away. He says that he asked himself what many would agree is a very reasonable, even necessary question: “what right do I have to tell this particular story?”

Then, in a turn so fortuitous it’s almost hard to believe (though I certainly want to believe) his wife, Tabatha, dug the pages out of the trash, read them, gave them back to him, and told him to keep going.

This speaks directly to the whole “no one writes alone” dilemma I wrote about in my last post, and is a truly heartwarming bit of myth-making, true or not. A fitting origin story for the “master of horror” who is still going strong in his 50th year as a professional storyteller (his latest collection is, for my money, his best in years). But it also gave us a new archetype. Or if not entirely new, than one that so precisely and effectively distilled certain adolescent fears, doubts, and conflicts that it has stuck with us in image and in thought nearly as much as Frankenstein’s Monster, or Dracula, or Grendel (well, maybe not him yet…but give Carrie a couple thousand years and we’ll see).

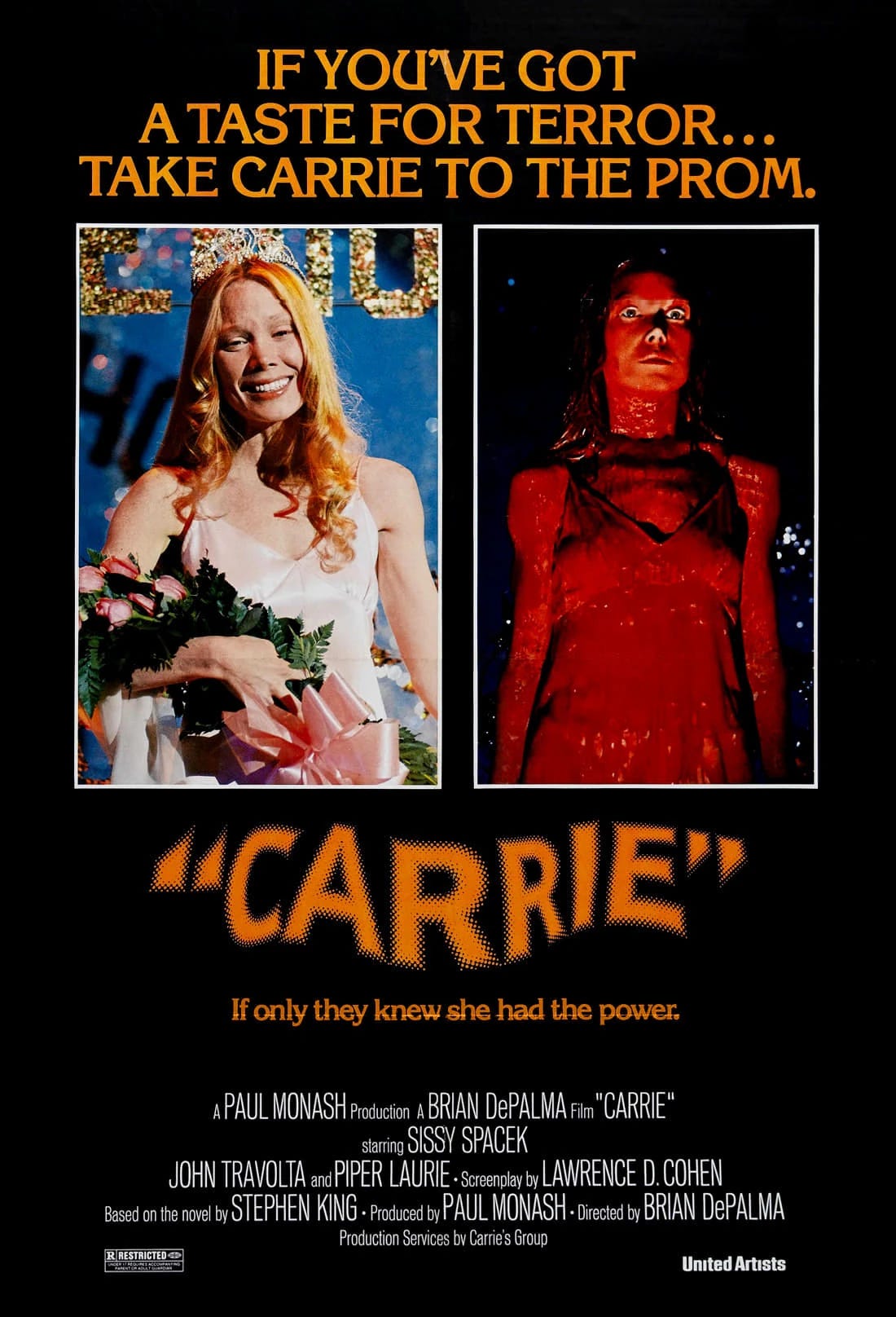

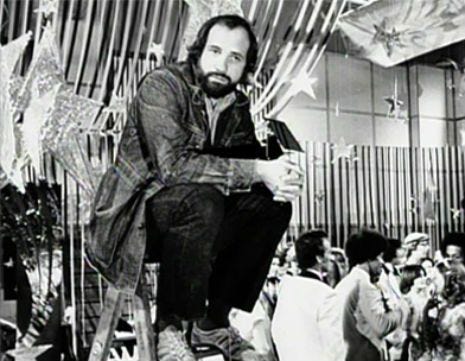

The book made a massive splash, but Brian De Palma’s excellent 1976 adaptation of the novel — starring the truly phenomenal, almost otherworldly Sissy Spacek — certainly helped to plant Carrie firmly in our minds, where she has stayed…and will stick around now that yet another new adaptation is planned, this time from Stephen King adapter extraordinaire Mike Flanagan, director of Gerald’s Game, Doctor Sleep, and the buzzy upcoming Life of Chuck, not to mention the very heavily ‘Salem’s Lot inspired series Midnight Mass.

…but we’re talking about De Palma here. A filmmaker deeply indebted to Hitchcock and committed to keeping audiences in bracing suspense, but one who is also willing to provoke them and turn their voyeuristic reactions against them (the opening credits are a perfect example of this tendency). A director who isn’t afraid to let the camera spin to the point of nausea, and who understands that the more he shows us of this young girl’s humanity - her hope to belong, her yearning to fit in, her desperation to be understood and accepted if only for a moment - the more fear she will ultimately inspire.

I want to be clear that I am not claiming that Carrie White is a monster, inherently. At least not at first. She would be better described as an innocent, sheltered and isolated, misguided by a cruel and maniacal parent, teased (tortured) by the people that ought to be her peers, even some of those who don’t have outright malicious intent (sound familiar, Frankenstein fans?). Oh, and she can move things with her mind. But even with that newly blossoming power, one that really does distinguish her from those around her (makes her one of a kind, at least in the narrow scope of her young life), she is not monstrous. Not at all.

By the end of the film, however, when the knives start flying and the fires are blazing and the prom-goers are screaming bloody murder, we can’t help but be reminded of the lineage of monsters that have been fixed in our minds by centuries upon centuries of stories.

What makes Carrie special is that if I really look at closely at the fear I am feeling when I see her in this moment - walking a through the carnage and mayhem with eyes wide and back straight - I understand that it is not Carrie I am afraid of. It is, as with Frankenstein, the position she finds herself in. It is the change she undergoes. Not from youth to adulthood, but from hopeful to hopeless. And hopelessness - like isolation - is perhaps more frightening than anything.

Carrie might have the big monster moment, but the true monsters in this movie are not Carrie herself, but those who force her into this hopeless position. The sadistic bullies - Nancy Allen’s Chris and John Travolta’s Billy - and her mother, played with truly unsettling brilliance by Piper Laurie, all seem to be doing their level best to ensure that Carrie remains an outcast.

But if I’m honest, the person I am most afraid of here - or rather the person I am most afraid to be - is Sue Snell, played in De Palma’s film by Amy Irving.

In the iconic opening scene, Sue is among those taunting and ridiculing Carrie as she cries for help. In fact, she’s right up there at the front. Laughing along. Not a care for the hurt her actions cause. But what makes Sue so interesting (and by extension what makes Carrie a pretty remarkable story, and more complicated than some may recall) is that she quickly, and authentically, feels regret for this action. True regret. While the other characters in the story plot ways to further hurt or hinder Carrie, Sue seeks a method of redemption.

George Saunders, another of my favorite writers, once said: “The things in life that I regret the most are failures of kindness.” The older I get, the more I agree with this statement, simple though it might appear. I remember with horrible clarity the times that I was mean or careless with the feelings of others. When what I know to be the ugliest part of me rose to the surface and took the wheel. There’s a feeling of helplessness that arrises along with these memories, and inevitably (unless we are truly cruel like Chris and Billy, and I do believe people like that exist) we want to know how we can, if not undo what’s been done, then somehow make amends.

And to her credit, Sue tries. She enlists the help of her boyfriend Tommy to take Carrie to the prom, show her a good time. And even though Tommy resists at first, he comes around to enjoying Carrie’s company the more time he spends with her. He comes to see her as a person when he actually bothers to look (what a concept). And it seems to be going well. It seems to be working. Sue’s guilt is not erased, but to a real degree countered by the joy she has helped Carrie to feel.

But then we see that bucket of blood. Perched to perfectly on the rafters above their heads, and we remember what kind of story we are in.

Rewatching Carrie is an exercise in inevitability, and, in a sense, helplessness. We know what’s going to happen. Like Sue, we can want to change it, want it with all out hearts, but in the end it doesn’t matter. The trap has been set. And the kindness that Sue and Tommy have extended toward Carrie is erased by the single tug of a rope.

No matter how many times you watch it, it will always be the same: the bucket of blood falls, and in that moment the wounded yet nevertheless hopeful girl we have come to know and care about falls away and all we are left with is a wide-eyed, slow walking figure of pure destruction.

I am careful here to write destruction, not vengeance. To me this isn’t justice, but tragedy, and I imagine any viewer would have a hard time cheering Carrie on in the moment. Especially once we see that the victims of her unleashed power are not limited to those who were cruel to her. Sure, the bullies get their comeuppance, but the guilty parties aren’t the only ones who suffer in the ensuing mayhem (her advocate gym teacher’s death in particular is a crushing blow, in more ways than one). There are movies about revenge if you want them, where the bad guys get what’s coming to them. But in Carrie, I can’t help but look on with a healthy dose of sorrow, even as Chris and Billy go up in flames (well maybe I like to see that, just a little). But more than I want any kind of violent justice, I just want Carrie to be okay. To have hope.

But in the end, it’s too late for her. It always will be.

It’s difficult to write about this film and its themes without falling into rote platitudes and moralistic grandstanding. Something I really admire is that both King’s book and De Palma’s film somehow never really feel like an after-school special. This is a highly moral tale in both versions, but never feels like a lecture to the audience to “be nice” or “do unto others…”

Instead it just feels like a portrait, or series of portraits, depicting cruelty, hope, kindness, helplessness, and finally…regret.

The final note of this film arrives when Sue, in a dream sequence, visits Carrie’s ruined home. While also being one of the all time great jump scares (it still got me this time and I knew it was coming), it is also a statement of what might be the film’s final and most poignant idea. Sue cannot escape what she did. What she failed to undo. Carrie is gone, but the cruelty she was shown by those around her is something they have to go on living with. A glossy, horror-show version of that thing that George Saunders was talking about. How our failures to be kind to others hurt ourselves, and never stop hurting.

At the risk of broadcasting my own neat and tidy “moral of the story” message here (which I have arrived at more for myself than for anyone who might be reading this) these monster movies, for all their differences yet striking similarities, seem to beam to me a simple message: you are not alone.

I don’t mind if that sounds too earnest. And I know that plenty of people will still find it odd that others find a sense of comfort and camaraderie and encouragement in such blood-soaked stories as these. But the more I think about it, and write about it, the truer it seems. Horror is a place we can go to better know our own monstrosity, in both its mutating and steadfast forms, and maybe fear it just a little bit less.

"How our failures to be kind to others hurt ourselves, and never stop hurting.", Nick struck me at the core. Recalling a middle-school image of a single cruel act that devasted another Carrie-like student has haunted me long into my adult years. No matter the acts of kindness and efforts of goodwill to reconcile my shame, the knowledge there is a little nugget of monster residing in some depth of my being, tamed to some degree by maturity, yet her power to undermine another still exists. This haunting truth that I compromised a personal value of compassion for another to garner some teenage measure of egoic power within has left me with deep regret and unrequited forgiveness.