There’s an old adage that nobody writes alone.

When I teach writing, I tell my students that this is absolutely true. I tell them that we all write with the help of others and learn from others’ examples. And then of course there are our readers—those other minds that we are always writing toward….but, if we’re being honest, when we write, we are mostly alone.

In my experience, writing most often occurs in a state of relative solitude. This is usually by design. I, for instance, like to write alone with the door closed, preferably in a tight, quiet space. I know lots of writers who write with music blasting, or in public places, or even with movies playing in the background, though I tend to prefer as little distraction as possible (something that can be tricky to come by). But beyond physical setting and the long hours spent in silence staring at a page that hopefully has something on it, it’s the life of a writer that often feels, in many ways, lonesome.

It’s not a feeling that’s exclusive to writers, of course. I suspect plenty of people feel this way about the work that they do (or aspire to do), but seeing as writing is what I know best, here’s what I’ve learned: writing is sometimes fun but always, always hard. It brings in a ton of rejection, and virtually no compensation or validation. It demands your time and attention wether you're at the desk or away from it, and makes you second guess nearly every decision you make. Many people who don’t write will always consider writing a hobby, or increasingly, an obsolete pursuit. And if you’re anything like me, you’ll wonder all the time whether the time you spend alone at a desk might be better spent elsewhere, or if chasing the infrequent joy of writing is purely self-indulgent, or at what point belief in yourself changes from ambition to delusion, or, finally, whether anyone besides you cares at all what you have to say.

That’s why what happened here on this Substack earlier this month really mattered to me. I had no idea that Substack HQ had decided to share my essay exploring anxiety and my thoughts on "The Birds” in their “Substack Reads” newsletter, or that someone (I’m not even sure who) had written a thoughtful introduction to it that caused so many new eyes to fall on this space. But I can now say confidently that this essay has been read more than anything I’ve ever written. Ever.

In a strange and backwards time where people too often measure themselves in likes and subscribers (notice the epidemic of recent Substack writers writing nothing more than “follow me I’ll follow back”), I feel a slight tug of embarrassment to admit that this moment meant something to me. But the fact that a few thousand strangers read my words, and that a handful of them took time to write that they appreciated what I wrote, made this work feel just a little less lonely. It was a much needed reminder that people like me actually are out there, right now, doing what I’m doing. Writing for virtually no one but themselves. Even though I’m still alone in the very same room (closet), that feeling of isolation has been (for the moment) dispelled.

Naturally, this good feeling was followed by a spike of panic. How to follow that last post up? How to capitalize? What lessons to learn? Why did that post garner attention where others went unnoticed? What was I doing wrong before? I’ve considered all those questions and then some, and I’m not sure there’s much point dwelling on them. I think the thing to do is just keep doing what I came here to do: put down in words the sometimes illogical, often conflicting, and invariably perplexing thoughts I have about the movies I love.

So, as the nights come faster and horror fans like me savor the last few watches of our favorite month, here’s what’s on my movie-mind this week: Monsters. Or rather, the behavior that creates them and the reasons they endure in our collective memory as objects of fear and, perhaps to an even greater degree, vessels of our pity.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is one of my favorite books. It’s not very long, but it is dense, and it took me a long time to read when I first tried it several Octobers past. The prose isn’t the kind I usually gravitate toward (fluid, but inescapably old-fashioned), and I can’t say I identify all that much with the main character (except perhaps for his obsessive tendencies). And yet, it remains one of my favorite books in large part because it is simultaneously one of the most famous books ever written and one of the most broadly misunderstood.

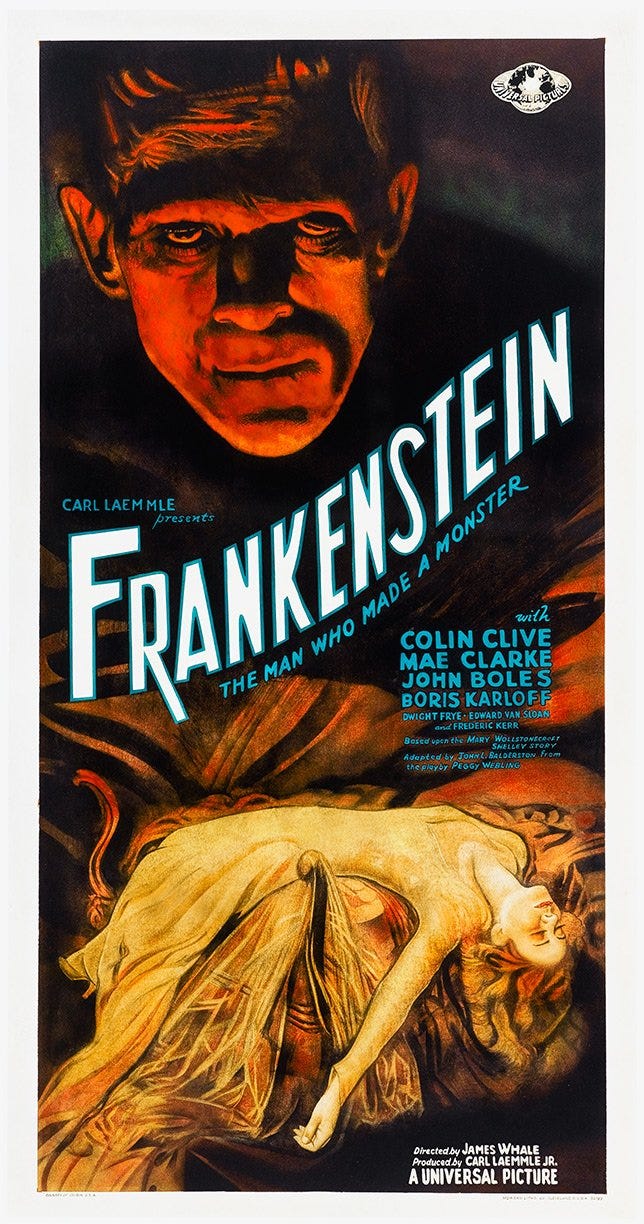

There are several aspects to the book that are virtually absent from our cultural understanding of Frankenstein, but the biggest one, and the one that really grabbed a hold of me when I read the book for the first time, was that the monster at the center of the story is nothing at all like the hulking, stomping, non-verbal monstrosity we have come to know and love. This version of the monster was an invention on the part of screenwriters Frances Edward Farrago and Garrett Fort (adapting a stage rendition by Peggy Webling), special effects makeup grandmaster Jack Pierce, director James Whale, and the great, “uncanny” Boris Karloff. This is where the flat top, neck bolds, forehead stitches, and too-small black suit come into the picture. The monster in Mary Shelley’s genre-spawning text, however, is an entirely different beast. Where Karloff and company’s monster looms and groans and strangles at will, Mary’s monster is articulate, calculating, vengeful, and absolutely overflowing with self awareness.

The monster in Whale’s film is undeniably iconic, to the point of being almost beautiful (in a morbidly statuesque sort of way), but he isn’t particularly scary to me, in part because we have been conditioned with a century’s worth of horror cinema to need a bit more to get truly scared, but I do find him disturbing. As I rewatched this classic (which is thankfully easy to find, and is now streaming on The Criterion Channel as part of an excellent Horror F/X collection), I tried to get down to the root of what I was really feeling about the monster. I watched him stumble here and there into largely accidental and clumsy violence, and quickly noticed that the moments when I felt disturbed arrived not when he was causing mayhem, but when he was himself afraid.

In the best scene in the film, Frankenstein’s monster comes upon a little girl tossing flowers into the water. She shares this little game with him, and we see him feel joy for the very first time (he has until this point in his young life only been examined, chained, tortured). When he runs out of petals, he does what seems to be the natural thing. He tosses the girl into the water. After all, in his world, she is a gentle thing, a beautiful presence, not unlike a flower. He simply doesn't know what consequences might follow. And when the girl drowns, we look on as he feels, for the very first time, guilt and regret and shame.

In this moment he is not so much a monster as he is in need of help. Of understanding of the world he has entered and his place in it. As he says in the book: “The world was to me a secret which I desired to devine.”

This is what makes him - or rather his predicament - so frightening. He observes his own wrongness, and has nowhere to turn to make sense of it. He is truly, unequivocally alone.

In the book, it is similarly not so much the monster that scares me, but the position he finds himself in. Shelley’s monster (referred to by Victor Frankenstein as the wretch, devil, creature, and simulacrum) acquires language by observing human behavior from a distance, and soon thinks deeply about his own existence, and through him Shelley gives us lines like this, which are impossible to imagine coming from the same monster Karloff made manifest on screens:

“Hateful day when I received life!' I exclaimed in agony. 'Accursed creator! Why did you form a monster so hideous that even you turned from me in disgust? God, in pity, made man beautiful and alluring, after his own image; but my form is a filthy type of yours, more horrid even from the very resemblance. Satan had his companions, fellow-devils, to admire and encourage him; but I am solitary and abhorred.”

It’s one of the things that surprises people most about the book, just how eloquent and introspective this reanimated corpse becomes. It doesn’t take long for him to see that he is inherently different from those he observes. That there is a barrier between him and the rest of humanity. He is burdened with the knowledge that he is wrong, that he should not be, and that he is truly the only one of his kind. And isn’t that something we all fear? Not that this being will get us, but that we might feel as he feels. It’s not fear sending that chill down your spine, but empathy.

It’s just a theory, and one that’s likely been written about for as long as we’ve been able to write the names of the monsters our minds invent, but that may just be what we find so endlessly fascinating about monsters. That they are the elevated embodiments of our deepest suspicions about ourselves. The things we believe we are when we forget we actually aren’t alone in the world.

As proof that this is an idea worth repeating:

1931’s Frankenstein wasn’t the first screen incarnation of the monster (see a flier for Edison’s 1910 silent “Kinetogram” short above) and it won’t be the last. That’s not conjecture, but fact. More Frankensteins are on the way.

Guillermo Del Toro - steadfast champion of the “lonesome, tragic monster” genre - recently finished filming his own version of this story, and based on images of a ship stranded in the ice, it looks like it might hew closer to Shelley’s vision than to Whales’s. Plenty of people noted that last year’s Poor Things was deeply indebted to Frankenstein, and you can see pictures of Christian Bale walking around in monster makeup alongside Jessie Buckley for Maggie Gyllenhaal’s upcoming The Bride.

We’re now over 200 years past the publication of Shelley’s novel, conceived as a way to pass the time and scare her poet pals during a winter storm, and there is still more this monster has to say, even when he says nothing at all.

…As I was drafting this post, the news broke that a new adaptation of another classic book turned classic horror film is in the works. This one also just so happens to be centered on a character of great power. One who is perhaps not inherently threatening, but who is pushed and pushed by those around them until their power becomes something to be feared, and not just by the wicked. Another kind of “monster.” Not born, but made:

Carrie White.

On Halloween, I’ll post the second (shorter) part of this essay, focused on another example of a seismic literary debut turned iconic film.

Hope to see you back here.

Thanks for reading.

I'll continue to post everything I write here for free, but if you’re interested in supporting me by becoming a paid subscriber….any little bit helps.