Angle On: Hungry Eyes

The Ensnaring Intimacy of "The Silence of the Lambs" (and "Stop Making Sense")

I recently moved across the country from my long-time home in Brooklyn, NY to Berkeley, CA. It was a big change, and while I can confirm that the west coast is a wonderful place with much to recommend it, there are times when I wake in the night missing certain irreplaceable New York delights. It’s true what they say about the scarcity of quality bagels, the public transit doesn’t hold a candle, and no amount of health food stores can compensate for the lack of bodegas complete with round-the-clock egg sandwiches and an enigmatic cat lurking on a high shelf. But of all the things I knew I’d miss (besides friends and family, etc etc) the thing I’ve been pining for most is a movie theater. More precisely, my movie theater.

Our last apartment was down the street from Park Slope’s Nitehawk Cinema (a welcome evolution from the ratty yet beloved neighborhood institution, The Pavilion). When I say down the street I mean the very same block. About a ninety second walk if you hustle. It’s a place I loved not just for its proximity but also for the constant stream of repertory and special screenings, unique pre-show reels, and stiff competition on movie trivia nights. I met friends there, had unique experiences and conversations, fell in love with brand new films and revisited old favorites. There’s never been an easier time to watch movies at home, and it’s great if all you want to do is witness a movie. But, with the help of a good theater, a movie can become an actual experience. It can make you feel part of something.

It’s been a good year for the health of the movie theater, which has been suffering a prolonged decline. The by-now-so-much-discussed-that-it’s-frankly-annoying “Barbenheimer” moment had a big helping hand in this, but there have also been a wave of great new films in theaters this year and more to come. But for me, the hands-down best experience I’ve had in a theater since leaving New York wasn’t a new movie at all. It was one I’ve seen countless times. Sounds and images as indelible as the taste of the air when autumn hits New York in full force. That film is “Stop Making Sense.”

Talking heads were a constant presence in my house growing up. Our tape of “Stop Making Sense” - Jonathan Demme’s now legendary 1984 concert film - was in perpetual rotation alongside a collection of their music videos, “Storytelling Giant”.

When “Stop Making Sense” was restored and remastered this year, I was eager to re-experience the film on a much larger scale, but wasn’t really prepared for what an experience it would be. I was bouncing in my seat (literally) singing along (at a totally appropriate and considerate level) and even saw a few people get up and dance in the aisles. When the lights came up, one of my friends said: “my face hurts from smiling.” I knew what he meant. I didn’t feel like I’d just watched something. I felt I’d been a part of something. Like I was really there.

This feeling I got, that a lot of people who are leaving their houses to watch this film on the big screen with a group are also feeling, isn’t just a byproduct of the idiosyncratic movements and infectious sounds of an ensemble of musicians performing at the top of their game. It is also the direct result of intentional, incisive filmmaking. It’s clear from the first moments of the film that its director, Jonathan Demme, understands on a basic, almost elemental level how a film can work to truly involve an audience.

There’s one moment that I really love (that comes shortly after David Byrne emerges in his iconic big suit) where he holds the microphone out toward the camera and stares at us. Right at us. This look, this gesture of invitation, is when I feel the air between the screen and my pupils dissolve.

As entertaining and seminal as this film is, Jonathan Demme is perhaps better known for a very different film. One that embedded itself in cultural memory so deeply that I was aware of its title and its characters well before I ever saw it. A film that could have easily, in other hands, been merely a solid - or just plain sordid - procedural thriller, but under Demme’s care became both a blockbuster and an unlikely award-season juggernaut - a feat that a horror film (if you believe this is a horror film which, I’ll grant, is debatable) wouldn’t accomplish again until Jordan Peele’s “Get Out.” That movie is “The Silence of the Lambs.”

Before the film drew audiences and gathered gold statues, Thomas Harris’ novel of the same name was an influential leap forward for popular crime fiction in terms of quality, complexity, and especially intensity. Lambs was a follow-up to Harris’ previous book, Red Dragon, which has also been adapted several times. The first was Michael Mann’s “Manhunter,” which is a great watch for fans of synth-drenched eighties vibes, and features Succession’s Brian Cox as a more subdued incarnation of Dr. Hannibal Lecter. But there is no denying that Harris’ dark, layered, surgically precise thrillers were best realized in Demme’s film featuring Jodie Foster, Scott Glenn, Ted Levine, and - of course - Sir Anthony Hopkins as Hannibal Lecter.

Despite being a hit on bookshelves, “The Silence of the Lambs” didn’t have the smoothest road to production. It was initially going to be directed by Gene Hackman, who also wanted to star…but in the role of Jack Crawford, as he supposedly found the role of Lecter to be just a little too dark. And he wasn’t the only one. The movie was passed from hand to hand, with most people finding the events depicted in the script too intense and graphic. That’s one reason it was a surprise to pretty much everyone that the perfect person to realize this harrowing story for the screen was the same guy who had, just a few years before, gotten people out of their seats and dancing with a man in a comically oversized suit.

But Demme was perfect, for just that reason. His proven ability to eradicate that space between the story up there in lights and you in your seat. To imbue this much, much darker film with the same immediacy and intimacy.

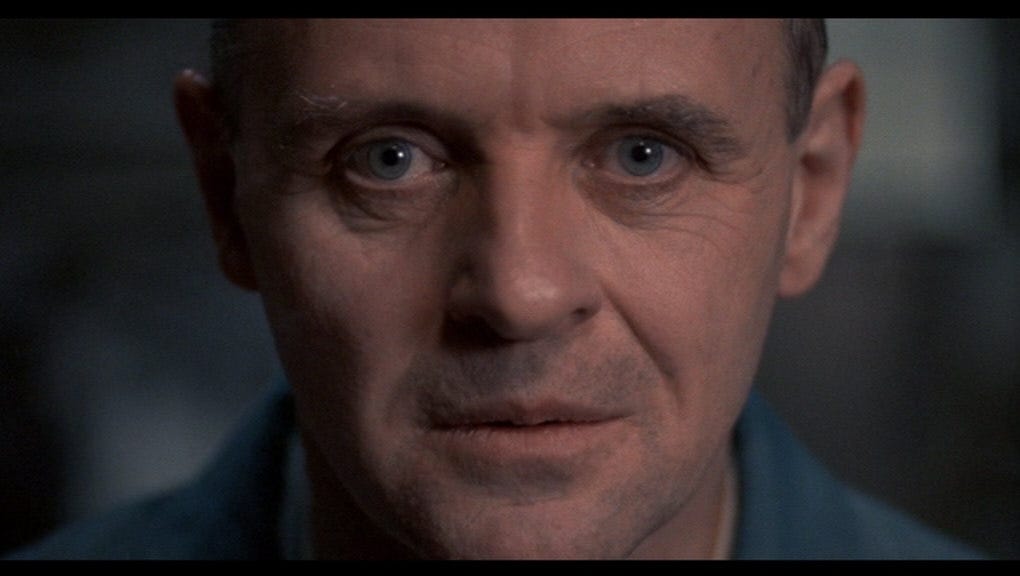

This is perhaps nowhere better exemplified than in an early scene where Clarice Starling, and we along with her, first find ourselves face to face with the well-mannered, monstrous, and undeniably magnetic Hannibal Lecter.

Look at this image (as if you could really look away). Now, look at it beside the image from “Stop Making Sense.”

On the surface there’s the obvious thing these two shots have in common: eye contact. Much has been written and said about the use of eye contact in the film. So much that I almost hesitate to repeat it, but in trying to get down to the root of why certain dark, uncomfortable, and even terrifying films keep us coming back for more, it’s impossible to ignore this simple yet incredibly effective choice to not just break the fourth wall but burn it to the ground.

For how intense and unnerving “Silence of the Lambs” is, it is an equally compelling and captivating watch. Each time I put this movie on (which I can’t help but do every few years) I’m apprehensive. I know what’s coming is nothing too nice, but by the end of the opening credits I’m again ensnared. Totally, helplessly involved.

This has a whole lot to do with Jodie Foster’s portrayal of Clarice, which - even from the wordless opening sequence - is layered with an incredible combination of fragility and strength. In the scene I mentioned above, Foster conveys an incredible mix of simultaneous fear, tenacity, and competence that is at least as impressive as Hopkins’ hissing and sinister winks. It also has plenty to do with the mood being created by Howard Shore (my favorite film composer by a pretty wide margin) and DP Tak Fujimoto’s tactile but undeniably eerie visual style (which has, along with the film’s structure, since been adopted by every other show on television). And this feeling of immersion only deepens as the story unfolds.

With each new stare - often it's men staring, directly at Clarice - we feel ourselves further steeped in her experience of the world. Despite the fact that Clarice is essentially a closed book, only opening up about her personal history and motivations after being pushed and pushed by the caged Dr. Lecter, I feel incredibly close to her. I can feel, to a great degree, what she must be feeling, even if she herself remains a mystery.

Come to think of it, David Byrne is a pretty mysterious figure. At least to me. His strange approach to lyricism is always as baffling as it is enchanting. And what's up with these outfits and dance moves? Is he intending to be funny, or is this serious art? Parody or pretension? Both? When I’m with him, really in the moment, those questions disappear and I feel I know him…even if I can’t fully understand him. I feel this same intimacy for (and with) Clarice. The way the world looks down, prods, judges, objectifies, underestimates, or ignores her. I don’t need to understand her…I kind of am her. At least while I am enduring the same pointed, unbroken stares. We are close. And in a cold world of cannibals and streaming services, closeness can be hard to come by.

This effect is earned by all of the creative forces - the acting, music, writing, visuals - working in harmony, but I’m suspicious that it’s Jonathan Demme’s incredibly considerate and penetrating eye that transforms both a relentless stage show and a meeting with a cannibalistic monster into such incredibly intimate encounters, and allows us to transform from simply viewers to active participants.

And “Silence of the Lambs” is a story that is all about transformation. Jame Gumb kills from an urge to transform (there are many great pieces on the complicated nature of this character and valid criticism of the portrayal written by others more equipped than me to tackle it, but this is a good one). Clarice hunts Jame so she can transform…and maybe quiet those screaming lambs in her mind.

The only one not trying to become something else is Hannibal. His acceptance of his own monstrous nature is something that both repels us and draws us in, makes us unable to do anything but meet that penetrating stare when it falls squarely on us, telling us it sees everything, way down to what we’re trying to keep hidden or hoping isn’t there. And in the end, the film holds on one final shot of Hannibal disappearing into a crowd, suggesting that not only are there monsters out there, but those monsters endure.

We know that we, not to mention the world around us, are in a state of constant change. Sometimes we get to choose how and when things change (move across the country, for instance), but most of the time we don’t have a say at all. In those moments it is a strange kind of comfort to look into the eyes of a charismatic and heinous killer like Hannibal Lecter, so certain of his place in the world. It almost feels good to pour yourself into those eyes for a little while. To be - not to put too fine a point on it - consumed.

Thanks for reading! “Anle On:” is a wholly independent endeavor. I’m so grateful if you’ve read this far, but if you want to show your support even more, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. If you do, you’ll be able to post comments - I’d love to hear your thoughts about this film and other cinematic moments you love/hate/love. You’ll also get to read some special short pieces that I’ll be posting in between the longer essays. I’m planning on making space here for other great writers to offer their thoughts on films they love soon, and your help would make that all the more possible. Thanks!